While pondering this recently I felt a desperate longing to join the list compiler's club. While staring at a print of Turner's Fighting Temeraire that I keep in my office at work it struck me that I could write about my ten favorite paintings. There are many people of both my close and nodding acquaintance who are much better qualified to analyze art than me (my cousin Jim who stops by occasionally is a fully paid up sculptor for instance, while Living on Less is an accomplished and witty graphic artist) but if Pete and Dud could pull it off, perhaps I can too. The paintings aren't in any particular order of preference, I'll just post whichever one I feel like writing about. Forgive me any digressions or faux pas; I may not know art, but I know what I like. First up:

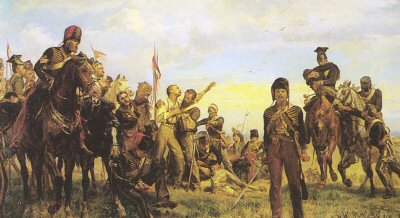

Lady Elizabeth Butler, painted sometime between 1874 and 1877

I was at a party this past new year's eve talking to a friend of a friend. In the course of the conversation she mentioned that she had just completed her master's thesis on Tennyson's poem The Charge of the Light Brigade. I mentioned that I had always thought of the poem as an anti-war piece of the tradition later expanded by Wilfred Owen et al during the First World War. She argued the opposite, stating (probably correctly) that the poem reflected the jingoistic and bellicose sentimentality of Victorian England. I kept going, pulling a theory out of thin air that given the social strictures of 19th century Britain, the criticism of the generals in the second verse ("Not tho' the soldier knew, Someone had blunder'd") was incendiary in itself and that the poem made a distinction between the folly of the commanders and the bravery of the doomed cavalry (a theme often alluded to in British war poetry, cf; Owen's "What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? - Only the monstrous anger of the guns..."). Then I wandered off to continue my demolition of a case of Sam Adams.

The next day, dealing with "the monstrous anger" of a killer hangover, I ran the conversation over in my head and my mind pulled forth the painting Balaclava from the recesses. I think perhaps that it was this work by Butler that made me think of Tennyson's poem as anti-war. However inadvertently, the painting certainly is an indictment of war to me.

I doubt Lady Butler intended it to be so. The wife of a British general, she specialised in paintings with an often glorious martial theme. Her more sombre pieces tend to deal with incidents like the charge of the Light Brigade or the escape from Afghanistan by Dr. William Brydon; examples of Britain's peculiar habit to turn military disaster into iconic moments of national pluck. In this painting however (showing the remnants of the Light Brigade [Hussars, Lancers, and Light Dragoons] returning from the disastrous charge during the Battle of Balaclava in the Crimean War) Butler has made a blinded Hussar the main focal point; in the background a Lancer holds a gravely wounded or dead comrade atop his horse while another cavalryman cries out. The painting does not show the suicidal charge at the Russian guns mounted on three sides of the onrushing horsemen ("Cannon to right of them, Cannon to left of them, Cannon in front of them Volley'd and thunder'd; Storm'd at with shot and shell, Boldly they rode and well, Into the jaws of Death,Into the mouth of Hell Rode the six hundred") or an battered but orderly aftermath of battle as in Butler's Roll Call. Rather, there is a canvas full of chaos, shock, pain, and death.

This may well have made the list not least because of dad's old hobby of making model soldiers (an obession I shared until quite late in my teens). Dad used to subscribe to a magazine called Military Modelling that used to regularly feature dioramas made in 1/35th scale of famous military paintings. One of the first projects, undertaken I think by a star in this very particular world called Sid Horton, was a recreation of Butler's Balaclava. The magazine showed the original painting of course, as well as a series of views of Horton's models, in particular the blinded Hussar (he's the one in the fur hat who looks a little like Timothy Dalton). Maybe because Adam and the Ants were big at the time or because I liked gold braid I was drawn to his pelisse but I soon found his staring sightless eyes burned into my brain. Ever since, I have associated this painting with lives squandered in a meaningless cause.

This painting is reflected back at me in photos of blinded gas casualties in the First World War, or in a Falklands War photo of a wounded Argentinian on the slopes of Tumbledown staring dumbfounded into the camera, or in the image of a howling, wounded American tanker aboard a Gulf War I medivac crying over the news of a friend's death. There are thousand more images that serve as a mirror to this painting and no doubt, sadly no doubt, there will be others too many to count.

So while Tennyson's words may be ambiguous on the page or in the ear, I humbly submit that when taken with Butler's painting they lose their dulce et decorum est pro patria mori gloss and turn to bitter ash in the reader's mouth. For while words can inspire people to embark on a search for glory in battle, images can often show the horrific reality of what "boots on the ground" really means. Which is why President Bush continues to make speeches but photos of returning caskets are not allowed.

Tennyson's poem:

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

"Forward, the Light Brigade!

"Charge for the guns!" he said:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

"Forward, the Light Brigade!"

Was there a man dismay'd?

Not tho' the soldier knew

Someone had blunder'd:

Their's not to make reply,

Their's not to reason why,

Their's but to do and die:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volley'd and thunder'd;

Storm'd at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

Flash'd all their sabres bare,

Flash'd as they turn'd in air,

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army, while

All the world wonder'd:

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right thro' the line they broke;

Cossack and Russian

Reel'd from the sabre stroke

Shatter'd and sunder'd.

Then they rode back, but not

Not the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volley'd and thunder'd;

Storm'd at with shot and shell,

While horse and hero fell,

They that had fought so well

Came thro' the jaws of Death

Back from the mouth of Hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honor the charge they made,

Honor the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred.

3 comments:

yeah, but what did you think of love monkey?

yeah, but what did you think of love monkey?

Love Monkey, Love Monkey, so good he asked it twice....

Post a Comment