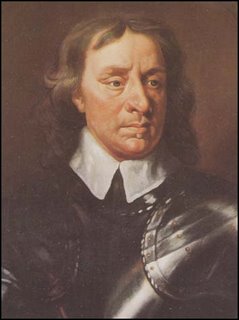

Peter Lely, c.1653

When I was a precocious, pretentious and extremist teenager I thought Oliver Cromwell was the dog's bollocks. To my binary-inclined adolescent brain the idea of an avenging pillar of East Anglian fire smiting the monarchy, religious sophistry, pomp, time servers, wafflers, and cant was peculiarly attractive. Like many teenagers trying to justify a political position, I jumped through all manner of hoops to either minimize or explain away the very dark, very 17th century nature of Oliver. Perhaps his words and actions did not provide a blueprint for my internal plans to take over the world, but his lack of prevarication and ruthless pursuit of his goals would come in handy.

As I got too old to be described as precocious and as I grew into a pretentious and extremist adult I found the contradictions of Cromwell more and more troubling. He was a republican who ruled as a king in all but name, a meritocrat who squashed the aspirations of the ordinary people, a benificiary of freedom of concience who unleashed sectarian slaughter, a soldier's soldier who betrayed his troops, and a parliamentarian who so gutted the institution he made the restoration of an expensive, illiberal, and hereditary monarchy a popular option. Unlike so many English radicals who are at heart conservative, yearning for the order of a simpler, mythical time of a fairer social order, Cromwell was a revolutionary. And like most revolutionaries, Cromwell's view of utopia and a new order spelled misery for many and was ultimately corrupted.

If I were to invent a time machine and travel back to the 1640s to meet Cromwell, he would have me imprisioned or killed for the contents of my head. He was the head of the English Protestant Taliban: if I had brought a sampling of modern American religious speech with me in my mythical time machine, Cromwell would find more comfort in the words of Pat Robertson than those of Martin Luther King.

Suffice to say, these days I only like parts of Cromwell and have taken the falling of the scales from my eyes as my cue for evaluating anyone I might carelessly describe as "a hero of mine".

So why do I still like this painting? Its less for the painting itself (it is hardly a remarkable portrait). I like it more for what Cromwell told Lely as he inspected the first version the Dutchman attempted, only to find that Lely had painted a traditional court portrait, radiant with heroism and divine munificence:

"Mr Lely, I desire you would use all your skill to paint your picture truly like me, and not flatter me at all; but remark all these roughness, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me. Otherwise, I will never pay a farthing for it."

If I only hold onto one Cromwellian aspiration for the rest of my life let it be this unflinching honesty about oneself, in examination of both the external and internal. Thanks Ollie, you magnificent, flawed bastard.

(Paintings 1 to 4 are here: #1, #2, #3, & #4. Half way to ten!)

4 comments:

I have to comment if only to agree with everything you just said. Agreeing with you is painful but I can't allow it to go unobserved.

I do love one of his famous quotes "I beseech you in the bowels of Christ, think it not possible you may be mistaken?" I always take this as the rule of absolute uncertainty. We cannot know everything. Nor should we. You, I, or they may, at any time be wrong. That gives me hope.

My word, Mondale and me in agreement. Tis the end times (more on that later).

"I had rather have a plain, russet-coated Captain, that knows what he fights for, and loves what he knows, than that you call a Gentleman and is nothing else."

Insanely radical for his day given his prominence. I wonder if he and George Washington would have got along (if I had access to my time machine). Probably not; too bad.

You British people learn about entirely too many odd people in school. You should be more like us. I couldn't tell you jack about most American historical figures and that's the way I like it.

Well Cromwell really wasn't that obscure for us- he laid the foundation of the modern professional army, orchestrated the beheading of a king who was believed by many to rule by order of God, cemented England's identity as a protestant country, and ruled as a dictator. But I get your point and I can assure you that Mondale, myself, and our peers are flattered.

The trouble with my secondary education, wonderful as it was, is that it allowed me to follow my own path that grew narrower by the year to the point where all I had in front of me was a choice of perhaps three or four majors and a lifetime of regretting that I didn't do more on economics, statistics, and languages.

We would have been luckier to have been born Finnish however: highest standards of educational attainment in Europe, and saunas.

Post a Comment