MANIC DEPRESSION: A CHAT WITH A ROOSEVELT ERA RELIC

Given the current economic climate many people are concerned that we might be living through a new great depression. Mindful of the saying “It is a recession when your neighbor gets fired, a depression when you do,” I decided to put current circumstances into historical perspective through an interview with Herbert Beal of Mooselookmeguntic, survivor of the original great depression and professional old man.

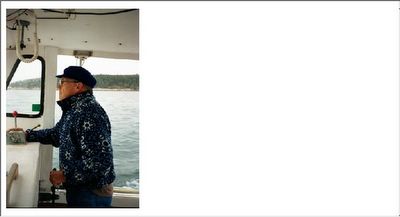

Herbert supplements his income modeling ugly fleeces for LL Bean

I met up with Herbert at the Big Puffin Farms gas station, as he indulged in his favorite pastime, frustrating the other patrons’ attempts to pay as he monopolized the register scratching instant win lottery tickets. I purchased two cups of scalding hot road tar from a pump jug labeled “Hazel-Mocha-Latte-Nut” and accompanied by Herbert, set up the tape recorder on an upturned Oakhurst crate over by the frozen dinners. The verbatim interview transcript follows below.

WW: Herbert, you were born in 1920, which made you of middle school age when the depression hit Maine. How were your school days?

HB: There were 6 students in my school back then. This, of course, was before the consolidation craze, so there were a lot of smaller schools. In our town of 400, there were 38 schools, all of which covered the full K-12 curriculum. I walked five miles to school and back every day of the year, if we had classes or not. It built character.

WW: What did your parents do for a living?

HB: My father operated a rickshaw, transporting visiting “sports” from Boston from the railroad station to their mountain top cottages. Mother was permanently in labor from the age of fifteen but she still found time to keep house and earn a little by extracting phosphates from bat guano for use in industrial fertilizers. We never had much money but we never saw ourselves as poor. That’s because we couldn’t afford a mirror.

WW: Did the depression really affect you, given that you lived in the country?

HB: The first clue we got that the stock market was in trouble was when a couple of stockbrokers from New York hired father to row them out on the lake and throw them over the side of the boat. The lake was frozen of course, so father smacked them on the head with an oar, ransacked their pockets, and buried them in the root cellar. Father blew all their cash on moonshine and went blind. He tried to keep up with his rickshaw business but thanks to his blindness he took a wrong turn and lost the rickshaw and his passenger over the side of Snipe Mountain. That’s when the depression hit home.

WW: How did you fare through the lean times?

HB: It was rough keeping clean, for one thing. In those days, winter lasted from November to October, so we were unable to bathe in the lake after they repossessed our bathtub. Mother would take us once a month to Mechanic Falls where we would use the communal dust bath. We would strip and flap our arms about like starlings. Then mother would delouse us with asbestos and sew us into our long underwear until our next bath.

WW: Were you able to eat well despite your poverty?

HB: We were luckier than most because we had a few chickens that gave us eggs. That said, we couldn’t afford feed for the chickens and so they got to eat the eggs. We ate the shells. Mother would slather the shells with Raye's mustard, spread the mixture onto a piece of her homemade clamato bread and call it “crackling jack,” but we weren’t fooled. In the twenties, lobster was seen as a poor man’s food so many Mainers got by on that. We grew up inland and didn’t have access to lobster, so we substituted raccoon. Kids these days have so much, but I bet not one of them has enjoyed a traditional Maine raccoon bake with all the trimmings.

WW: The trimmings?

HB: You know: baked horse apples, fiddleheads, steamed poison oak, fiddlebottoms, dump clams, outhouse corn, and fiddlebits.

WW: Where was the government throughout all of this?

HB: Governor Baxter missed the depression, as he was obsessed with his “Underwood Typewriter” program, which was intended to give every seventh grader in Maine a typewriter until graduation. The Maine legislature was busy trying to water down the Governor’s plan for “Baxtopia,” his own private country in the North Woods. The federal government mistakenly thought Maine was part of Canada and refused to help.

WW: So you were basically on your own then?

HB: When I was in the sixth grade, I had to quit school and take a job. I left Mooselookmeguntic and walked to Farmington, a trip that took me eight weeks as my sense of direction had been impaired by generations of inbreeding. I worked as a delivery boy for Mr. Goyle, the mortician.

WW: A mortician’s delivery boy?

HB: In those days people paid for funerals by installment. As the depression set in, many people died early, before they had made full payment. Mr. Goyle was a fair man and would take the body on consignment and give the family a month to pay the balance. If they paid, the funeral went ahead. If they defaulted, they got the body back. It was my job to return the merchandise.

WW: How did you go about that?

HB: I had a delivery bicycle. We would load the casket into the basket, and I would pedal off to make a delivery. Of course, times were hard and we had a lot of returns, so Mr. Goyle was unable to pay for a decent bike. My bike was a big old Schwinn but it didn’t have any wheels.

WW: How did you manage?

HB: We were made of sterner stuff back then. I would sit and pedal like mad, basically dragging the bike and casket down the road by force of will. Without the wheels, the bike was low to the ground, and I would be constantly banging my knees on the underside of the handlebars. Without wheels, the mudguards would drag along the road, sending up a shower of sparks. Everyone would know it was me when I cycled by. “Look!” They would shout, “There goes ol’ Sparky Bleeding Knees the Corpse Hauler!”

WW: We should wrap up now Herbert, but one last question: when did the depression end for you?

HB: The good times came about with the start of World War Two. With my knees so badly damaged from the handlebars I was rated 4-F and instead served my country as a gigolo in the greater Portland area, comforting the wives of absent servicemen. After the war I went to college and trained as an aromatherapist. I still eat “crackling jack” to stay humble though.

WW: Herbert, thank you for your time.

HB: On your way out, grab me a couple of “Lucky Lucianos” and a “Waste-a-Dollar” scratch tickets, will ya? I need to get back to frustrating my fellow patrons.

No comments:

Post a Comment